A white “wonder paint” that reflects 98 per cent of the sun’s rays could help homeowners slash their summer power bills.

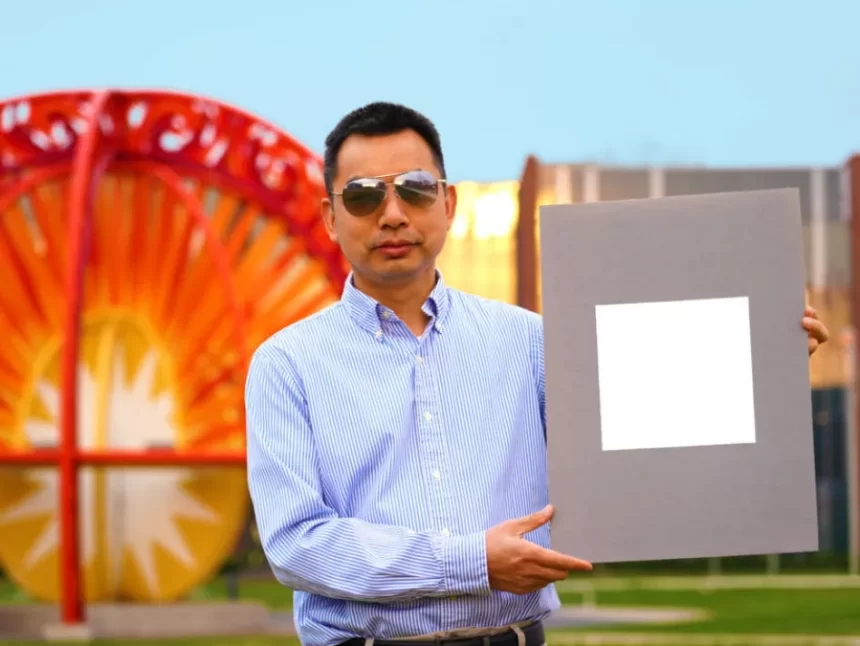

Invented by Purdue University Professor of Mechanical Engineering Xiulin Ruan, the white paint is designed to cool down buildings and prevent global temperatures from rising.

“If you were to use this paint to cover a roof area of about 1,000 square feet [93 m2], we estimate that you could get a cooling power up to 10 kilowatts. That’s more powerful than the air conditioners used by most houses,” Ruan said.

When applied to the roof of structures, the paint cools down surfaces as much as five degrees Celsius during the day and up to ten degrees cooler at night, according to a report in The New York Times.

Scientists consider paints like this transformational for cooling down the planet and reducing electricity use, as buildings with this kind of white paint could cut down on their air conditioning by as much as 40 per cent.

The innovation is leagues ahead of any commercial white paint currently available on the market. Paints that claim to be ‘designed to reject heat’ can, at most, reflect only 80 – 90 per cent of UV rays and fail to cool down surrounding surfaces.

Ruan’s white paint is so effective at reflecting sunlight that it even works during winter. In an outdoor test with an ambient temperature as low as six degrees, the paint still managed to lower the sample temperature by almost five degrees.

Ruan and his team say the paint is the result of six years of research building on work dating back to the 1970s when scientists first conceived of cooling paint as an alternative to traditional AC.

World record holder

The research team believe that this new “whitest white” may be the closest equivalent to Ben Jenson’s “Vantablack”, which absorbs up to 99.9 per cent of all visible light.

In 2021, the Guinness Book of World Records named it the whitest paint on earth. But Ruan said that wasn’t the goal.

“We weren’t really trying to develop the world’s whitest paint,” Dr Ruan said in a statement provided to Build-it.

“We wanted to help with climate change, and now it’s more of a crisis and getting worse. We wanted to see if it was possible to help save energy while cooling down the earth.”

According to the team’s predictive models, covering only one per cent of the earth’s surface in the paint could mitigate the “total effects” of global warming.

This has spurred the team to make the paint applicable for surfaces outside of the home, including asphalt and roadways.

Last year, Ruan announced that he had invented a version of this paint that can be applied to vehicles.

Unfortunately, the paint won’t be on sale for about another year as researchers are working on improving its durability and resistance to dirt.

Despite the expensive development, Ruan reassured homeowners that the cost is expected to be similar to current commercial paint.